I remember the first time I had to fit a bass bar. I was certain it was impossible. It took me multiple days and a lot of coaching from my teacher. Now it’s just a morning of concentration from start to finish. When you are first making violins technical tasks—such as fitting two surfaces together or even sharpening your tools—seem by far the most difficult. But eventually you get the hang of them. That doesn’t mean they are actually easy, just that they are a specific kind of hard that takes a certain kind of learning and practice to get better at. Different parts of violin making are hard in different ways. But for all of them learning and practice help face the challenge; there is no magic or innate skill here. And I think all craftworkers would agree that it’s always a continuous process that doesn’t really end.

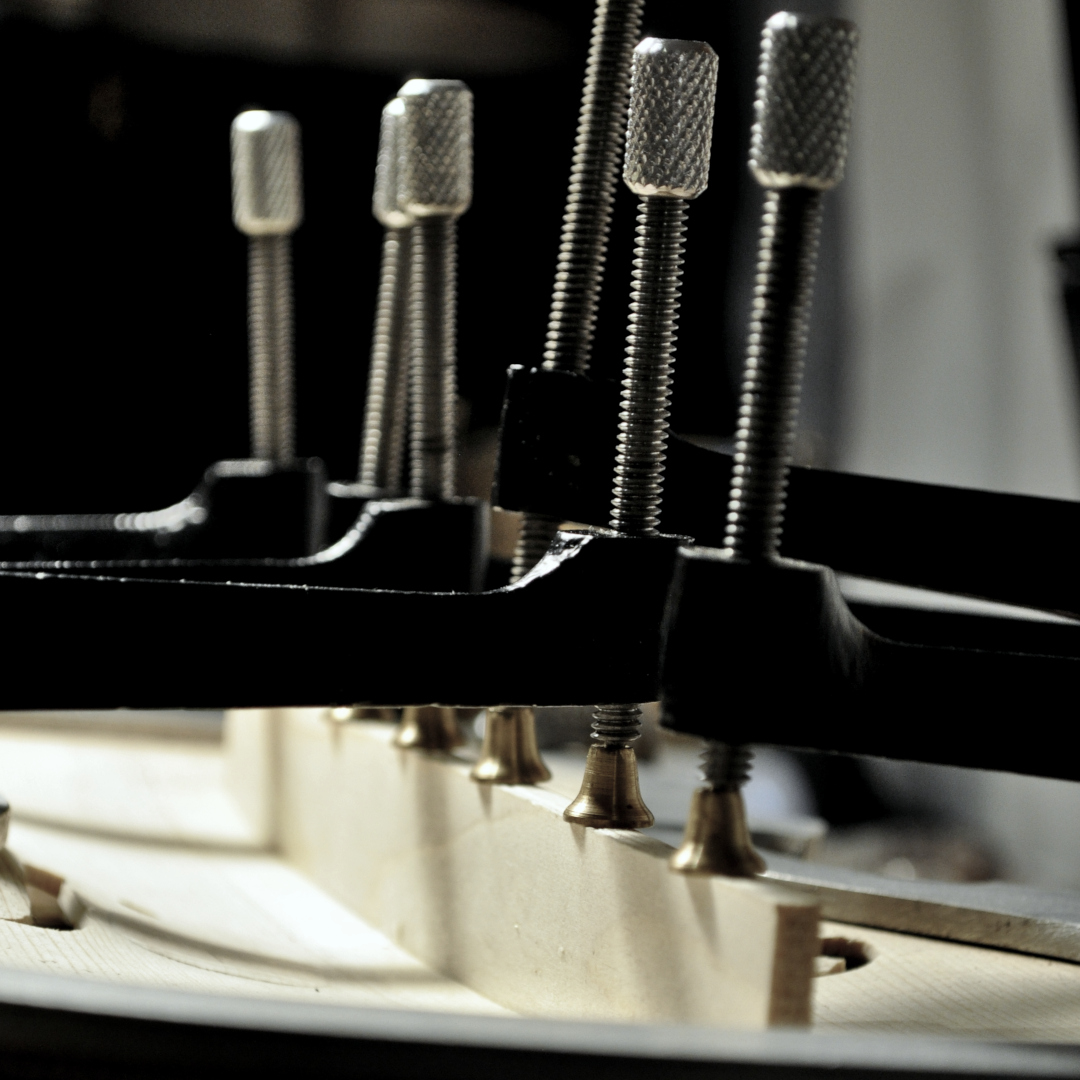

Glued and clamped

Halfway to its final shape

These days, I would say one of the most difficult steps of making a violin for me is carving the arching of the top and back…specifically: deciding when to stop. In fact, it might be the single most difficult step in making a violin.

The challenge stems from there not being a clear right or wrong answer. For example, when carving a bridge either the feet fit or they don’t. The arching, however, is a complex three-dimensional shape with a range of plausible answers. Creating those shapes is less about hitting a set goal and more like trying to embody an abstract concept.

That means I don’t have a single ideal arching that I’m trying to duplicate. It’s inherently tricky to see, take-in, and hold in one’s mind the whole complex shape at once. It’s possible to take measurements in a few spots here and there, or to compare some select segments to a template. But that kind of approach that will only ever get you so far. And because it all flows together, changes and corrections in one area necessarily affect the shape in its entirety. Any deviation, even a small one, from your ideal platonic model would require a whole series of adjustments to make everything fit and flow together again so as to end up with a coherent whole.

So instead of a static model of the goal I have a bunch of ideas about how I think the arching should work. All those ideas end up interacting both with each other and with the specific outline, wood, and other details and factors in front of me. To be perfectly honest, it’s a jumbled mix of intuitions, concepts, sense memories, guidelines, images, and also a few stray measurements. Together they help me evaluate whether or not I am on the right path. But, there is no preset end to that path. That’s why knowing when to stop is so difficult. The line between just right and too far is both thin and ill-defined. And, of course, there is no way at this point in the construction to directly evaluate what actual matters: the final sound of the instrument.

At the end of the day, sometimes you just have accept a little bit of uncertainty in life. Luckily for me, this won’t be the last violin I build. My experiences from this instrument will help build and refine my arching concepts for the future. For me, this kind of working out of an abstract concept on and through a physical medium really goes to the essence of what it is to be engaged in a craft.

And the arching isn’t just important for the sound. It’s also important for getting the ff-holes right. Laying out ff-holes can be a trip. You might think it’s a straight forward matter or correctly positioning a template so as to meet a few simple constraints. But no. Really you are projecting a funky two-dimensional shape onto a complex curved three-dimensional surface.

The ff-hole you start with and the ff-hole on the instrument are never actually the same. Making even small adjustments to their location or orientation can alter how it looks and its relation to its surroundings in surprising ways. It’s like walking past a fun house mirror trying to find the sweet spot where everything comes out just so. Plus, it all depends on the underlying arching you carved. Even slight asymmetry, a small dip or wave, or just a different flow from usual can make it very difficult to get the ff-holes to sit well on the plate. Sometimes it feels like a puzzle without a solution. But, once everything falls into place they are deeply satisfying to behold. Then again, once they are laid out, it’s time to actually carve them.

Carving ff-holes takes faith. After the initial rough sawing they look ugly. They look scary. They don’t look like ff-holes. I always have the same thought: what if this time I can’t make them look right? But you have to pick up the knife anyway and carefully and slowly begin to remove a bit of wood here and a bit more wood there. There is no guarantee that you’ll end up with a nice ff-hole and not some molten gaping horror. Can’t let that stop you. Sometimes I have to remind myself that I’ve done it before, and that I’ve sharpened my knife well, and that my hand is following my eye. Can’t stop even if you want to because what use is a top plate with a partially carved ff-hole? So you keep carving and making it look a little bit better and a little bit closer to how you want it.

It can be frustrating. That’s why I have a post-it on my toolbox to remind myself of what to do when it gets overwhelming:

- Go have some tea.

- Sharpen your tools.

- Make a small thing a little bit better.

But then, once you get one ff-hole looking pretty good there is always the second one—and now it has to look not just good, but more or less similar to the first one!

But at least while carving ff-holes you can make nice, more or less linear, progress from not-an-ff-hole towards your goal. Carving scrolls takes a different kind of faith.

Craft is most pleasant when you are able to make steady progress towards your goal. And that works for most things. Not scrolls. Scrolls—at least to my mind—take a detour through an ugly phase. You can layout everything nicely, work everything into a nice initial form, and then…there’s a point when the shapes don’t quite make sense anymore and you have weird extra bits of wood and ragged spots that you will, of course, clean up later but right now it doesn’t make much sense to deal with. It always comes together at the end. But to get there you have to maintain your faith, not in your hand skills and tools like with the ff-holes, but in the steps and process that will get you from A to B, and ultimately to C, a good sounding instrument that a musician will enjoy using to produce music.

But that’s just how craft is: Faith and uncertainty, mediated by hand and tool.